Politics

CONTROLLING THE MARGINS

The sample text below is an extract from a chapter in the third section in the book. For a full list of the book’s contents please see here.

Chapter 15:

The China-Tibet Conundrum

Ranjit Singh (1780-1839) wrested control of the Punjab from what remained of Ahmad Shah Durrani’s force of occupation, expanding his territory north to Kashmir, west to Peshawar, south to the Sindh, and threatening the British to the east. He created a fearsome army with the help of foreign mercenaries, notably French, and enjoyed the company of curiosity-seeking European travellers. Painting by Alfred de Dreux, 1838.

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Stéphane Maréchalle.

It seems almost incredible in hindsight that one geopolitical earthquake could be followed so closely by a second, equally or perhaps even more profound. Two years after Indian Partition, in 1949, the Chinese communists under Mao Zedong ousted the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek after a long and bloody civil war and established the People’s Republic of China. Almost immediately, Mao resurrected China’s expansionist ambitions, supporting the North Koreans against the south in the bloody war that would soon erupt and eyeing the vast expanse of Tibet to the west.

On October 25, 1950, barely a year after the Communist victory, the New China News Agency peremptorily announced:

Whose imperialism, one might be tempted to ask. But ‘liberate’ Tibet, the People’s Liberation Army proceeded to do with ruthless efficiency, first attacking the eastern Tibetan provinces of Kham and Amdo and reaching Lhasa in September 1951. To put a gloss on the proceedings, the Chinese drafted a Seventeen-Point Agreement handing themselves a carte blanche and bullied a five-man Tibetan delegation, which did not include the sixteen-year old 14th Dalai Lama, into signing it. With the rest of the world on the side lines trying to assimilate what was happening, the Chinese annexation of this mainly pacifist and religious theocracy proceeded apace.

The Chinese have long argued that Tibet has historically always belonged to them, but plenty of historians, diplomats and friends of Tibet are more than willing to argue the opposite. Alas, none of them had the power to reverse the events triggered in 1950.

What is certain is that the history of China and its relationship with the Tibetan people is centuries long, highly convoluted and legally ambiguous, at least in terms that make sense in modern times. In short, there is endless scope for debate. Phrases and words such as ‘patron-and-priest’, ‘suzerainty’ and ‘sovereignty’ tend to be bandied about as though they might by some miracle provide a flash of clarity. But reasoned argument never stands a chance faced with the brute force of realpolitik. Empire builders from the Romans to the British understood that, just as China does today.

Ironically, during the time of Tibet’s early kings, the tables were reversed. Tibet was the empire builder. Not yet Buddhist, Tibetan warriors overran vast swathes of China including its ancient capital at Xi’an, most of today’s Sinkiang, and many areas of the Himalaya south of the main watershed. Later, as Buddhism was imported from India, its widespread adoption compromised Tibet’s fighting spirit, and territories were progressively lost.

The Hunza region north of Gilgit proved the last major obstacle to British domination of the northern areas. In 1891, a force of 1,000 Kashmiri and Gurkha troops, led by Colonel Algernon Durand and sixteen officers, departed Gilgit, marched up the Hunza river and took the seemingly impregnable Baltit Fort in the Hunza valley.

Noradoa / Shutterstock.

On the other hand, Buddhism provided an exalted spiritual status that served them well when the Mongol hordes came visiting in the late 13th century. The Mongols may have boasted military power, but for their spiritual needs, and especially for magical cures proffered by visiting religious figures, nothing could beat a Tibetan lama. Throughout the Yuan dynasty, founded by Kublai Khan in 1271, the two parties enjoyed a snug duality. The Mongols acted as patrons to Tibet, in terms of wielding any necessary military protection, while Tibetans provided the Mongols with much sought-after religious instruction. No territory of either party was apparently claimed by the other. To neutralize the current Chinese claim that they have always controlled Tibet, some of today’s more wily commentators also like to point out that the Mongols were hardly Chinese, they were Mongol.

Ranjit Singh’s youngest son, Maharajah Duleep Singh, aged seven, presenting himself to Lord Hardinge in March 1846 inside the Lahore Fort to sign the Treaty of Lahore. This effectively ceded control of the Punjab to the British. The terms included the requirement that the Lahore Durbar relinquish the Koh-i-Noor diamond. Engraving by H. K. Browne and R. Young, ca. 1850.

Georgios Kollidas / Alamy Stock Photo.

When the Han Chinese re-established dominance from the Mongols in 1368, creating the Ming dynasty, the patron-and-priest scenario continued, and although current interpretations of this relationship vary dramatically depending on their provenance, both China and Tibet seem to have pursued fairly independent paths.

It was with the arrival in 1644 of the Manchus, a Chinese tribe living in Manchuria, and their displacement of the Han Chinese to establish the Qing dynasty, that the Chinese-Tibetan relationship becomes more contentious. At first it was all politeness and respect. The great 5th Dalai Lama, who did so much to open Tibet to the outside world, honoured an invitation from the Chinese Emperor travelling to Beijing in 1652 accompanied by 3,000 men. Some commentators claim that the Emperor treated him as an equal, while others, typically Chinese commentators, would say as a vassal.

Less debated is the outcome of a crisis developing some seventy years later when the Manchus marched on Tibet to suppress continuing interference by Mongols from the north in not just the Tibetans’ affairs, but by contagion also their own. By 1728, the Tibetans had accepted and were even welcoming these Manchu forces as a permanent deterrent against the Mongols, as well as the presence of two Manchu Residents, called Ambans, who commanded the Manchu troops. The Manchus further strengthened their hold on Tibet when they proved instrumental in repelling two invasions of Tibet by Nepal, in 1788 and 1791. They would be on hand again, in 1841, to squash Zorawar Singh’s attempted invasion from Ladakh.

Throughout this period until the mid-19th century, the Manchus remained a force to be reckoned with, and the Tibetans indeed lapsed into a relationship with their Chinese overlords that can only be described as subservient. However, there were no treaties as such, no agreed terms to place the relationship on a legal footing. The Manchus did not even refer to Tibet as a province, which was the case for Chinese Turkestan and Taiwan. Moreover, the patron-and-priest connection endured. The Chinese as well as the Tibetans revered the Dalai Lama as a living deity. However, as the Opium Wars and Taiping rebellion sapped Chinese energy and resources, their hold on the more remote corners of their Empire began to weaken. In Tibet, the resulting political vacuum simply fanned the suspicions of those two main players in the Great Game, Britain and Russia, each suspecting the other of subverting Lhasa to its own ends. The British in particular were running out of patience.

Two of the most prominent Great Game players, Viceroy Curzon and Colonel Francis Younghusband, precipitated an expedition to force open Tibet, ostensibly for trade but also to offset Russian influence. The photograph shows Younghusband’s expedition stationed at Gyantse Jong (Fort) in June 1904. The fort was taken after fierce resistance with many Tibetan casualties.

© Royal Ulster Rifles Museum, Belfast.

Attempts by the British to engage diplomatically with Tibet, or develop trade with the country, met with systematic rejection. Tibet remained resolutely closed, and only through subterfuge could Montgomerie’s pundits continue to enter and explore the forbidden kingdom. Westerners were totally banned, and any Tibetans found providing them assistance were harshly punished or put to death. And all the time, it seemed, Russia was on the point of grabbing this last great prize of Central Asia. It was time to act, and two men with like views on the matter would not hesitate.

Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India since 1899, was always pushing the Great Game agenda, albeit to the alarm of his masters in London, and his man, Colonel Francis Edward Younghusband, one of the most seasoned of players in the Game, was more than ready to force open Tibet as soon as Curzon gave him the green light. And force it would take.

Chinese Vice-Premier Chen Yi, the 14th Dalai Lama and the 10th Panchen Lama review a Tibetan guard of honour wearing Chinese army uniforms in May 1956. By now, the uneasy truce between the Chinese and Tibetan governments was slowly breaking down.

AFP / Getty Images.

In 1903, London gave muted approval for a small expedition charged with opening trade and clearing up a minor border problem.

Younghusband wrote immediately to his father:1

Younghusband set off with over 3,000 soldiers and an even larger accompanying retinue. Strung out along the Chumbi valley, a key trade route between India and Tibet, the expedition languished as Younghusband waited in vain for Tibetan representatives to materialize for a parley. Eventually, in the absence of any engagement by the Tibetans, he was ordered to proceed to Lhasa. Soon the expedition was threatened by hordes of poorly armed Tibetans. The ensuing engagements were a bloodbath, shocking even Younghusband.

The expedition nevertheless pushed forward reaching Lhasa on August 3, 1904. Younghusband imposed a treaty on whatever remained of the Tibetan government — the 13th Dalai Lama had fled north by this time — including trade agreements between the two countries and a clause forbidding Lhasa to offer concessions to any foreign power but the British. Younghusband and his expedition then retreated. Of the feared Russian influence in the Tibetan capital there was no sign.

Curzon later pushed for Tibet to be recognized as an independent country, but the British Government instead supported the notion that China historically exercised some degree of suzerainty over Tibet, or at least over Amdo and Kham, the eastern parts of Tibet immediately bordering China. Perhaps this encouraged the dying Manchu empire to indulge in one last Tibetan fling.

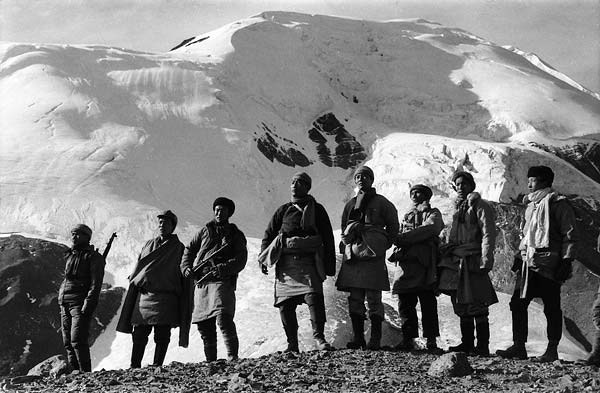

In 1956, the CIA committed to assisting the Khampa guerrilla campaign against the Chinese occupation of Tibet. In the 1960s, the Americans helped set up a major base for guerrilla activity in the remote area of Mustang in north-west Nepal. The photograph shows the leader of the Mustang force, Gyen Yeshe, and the overall operations chief of the Khampa campaign, Lhamo Tsering (fourth and fifth from left). They stand with other guerrilla commanders at a pass overlooking Tibet in the early days of the Mustang operation.

© Lhamo Tsering Archives.

In 1910, no doubt provoked by the British incursion, the Manchus summoned up the energy to impose themselves one last time on a land they had long considered their own. This time the Dalai Lama fled south to Sikkim, enjoying the hospitality of Charles Bell, the British Resident there; we met Bell earlier in ‘A Different Type of Reality’. A mere one year later, however, it was all over. The Manchus were ousted by the revolutionary movement of Sun Yat-sen, and for the next three decades, as China endured years of revolution, civil war, and oppression by the Japanese, Tibet would at long last be left to its own devices.

In 1913, Tibet declared itself an independent state. In the words of Hugh Richardson, the last British Officer in Lhasa and passionate advocate of Tibetan independence, “There was not a trace of Chinese authority in Tibet after 1912”.

That same year, the British continued to try and impose its authority on the region by summoning a tripartite conference between Tibet, China, now a Republic, and Britain at their summer capital in Simla. The conference was chaired by Sir Henry McMahon, foreign secretary of the British Raj. The main objective was nothing less than defining once and for all the boundaries and legal relationship between Tibet and China ….

[BUY THE BOOK TO READ ON]