Religion

A DIFFERENT TYPE OF REALITY

The sample text below comes from the second chapter of the first section in the book. For a full list of the book’s contents please see here.

Chapter 2:

A Buddhist Renaissance

Tsongkhapa (1357-1419) founded a lineage that favoured intellectual rigour over mystical ritual. His reincarnations became known as the Dalai Lama and would come to dominate Tibet in politics as well as religion. Two great monasteries at Drepung and Sera, near Lhasa, were built by his followers. This is the first of fifteen thangkas illustrating how, throughout his previous lives, Tsongkhapa cultivated the path to enlightenment.

© His Eminence Tsem Tulku Rinpoche.

It was Vajrayana’s ability to absorb ever more deities into an already complex cosmology, plus more than a hint of magic, that gave Padmasambhava, or Guru Rinpoche, the leg up as he progressed towards Lhasa battling and subduing Tibet’s local demons.

Around 775 CE, still in the reign of Trisong Detsen, Padmasambhava and Santaraksita inspired the foundation of Tibet’s first monastery at Samye, a settlement not far from where the Yarlung River opens out into the Tsangpo valley. It was built along the lines of a famous monastery in Bihar, India, with four walls arranged to mimic the layout of a mandala. Its three storeys were designed respectively according to Indian, Chinese and Tibetan styles, a medley that mirrored the disparate influences on Buddhism’s introduction in Tibet. The country was still heavily reliant on gurus and texts from both China and India.

In 792, Trisong Detsen felt compelled to choose whether to follow Indian or Chinese teachings and launched a great debate to help him decide. Over a period of two years, with representatives from both sides positioned either side of the Tibetan king, philosophical arguments were batted to and fro. In the end, the result was influenced as much by political concerns as religious argument. While the king wished to protect himself from a newly aggressive China, India lying beyond the impenetrable Himalayas seemed to pose little threat. An acolyte of Santaraksita, called Kamalasila, who was invited to present the Indian case won the day. Trisong Detsen subsequently forbade his subjects to follow Chinese teachings, and Kamalasila remained in Tibet to move the Indian teachings forward. The opposing camp nevertheless plotted revenge. Four Chinese butchers were dispatched to kill Kamalasila, which they accomplished by ‘pinching his kidney with their hands’. Kamalasila’s body was embalmed and placed in a monastery twenty miles north of Lhasa, where it remains to this day. By the time Trisong Detsen died, around 797, the ruling class remained committed to the Indian, and not the Chinese, form of Buddhism. And Tibet as a whole continued to enjoy a golden age with its still vast territories.

But there would be one more fight.

Trisong Detsen’s two grandsons, nicknamed Ralpachan (Long Hair) and Langdarma (Mature Bull), had very different views on the new religion. Ralpachan’s inclination was to accelerate the move to Buddhism, favouring monks above everyone else, even allowing them to walk on his hair, a sign of his professed abasement. He also introduced systems of weights, measures and coins based on what had been learned from India. But for some, he was going too quickly. In particular, he failed to gauge his brother’s attachment to the ancient deities of Tibet, which in rather loose terms were grouped under a belief system called Bon. Scholars today cannot agree exactly what Bon looked like in these early days, but over the centuries it cunningly evolved to resemble, even duplicate, Tibetan Buddhism, with obvious name substitutions for Buddha and the key deities. It is now so close to Buddhism as to be a sect now accepted by the current Dalai Lama.

With the brothers at loggerheads, a religious war broke out. Ministers faithful to Langdarma killed Ralpachan by ‘twisting his face down towards the nape of his neck’ — there was no lack of imagination when it came to killing people. Langdarma took over the reins of power and promptly disbanded the monasteries and forced celibate monks to marry.

In 842, Langdarma himself was assassinated by a Buddhist monk. Tibet now entered a period of political and religious turbulence. Followers of Buddhism were reduced to hiding their sacred texts in mountain caves around Lhasa. And the desire for empire among the nobles became compromised by a non-violence ethic that Buddhism had begun to instill in the country. The glory days of the early kings were beginning to fade.

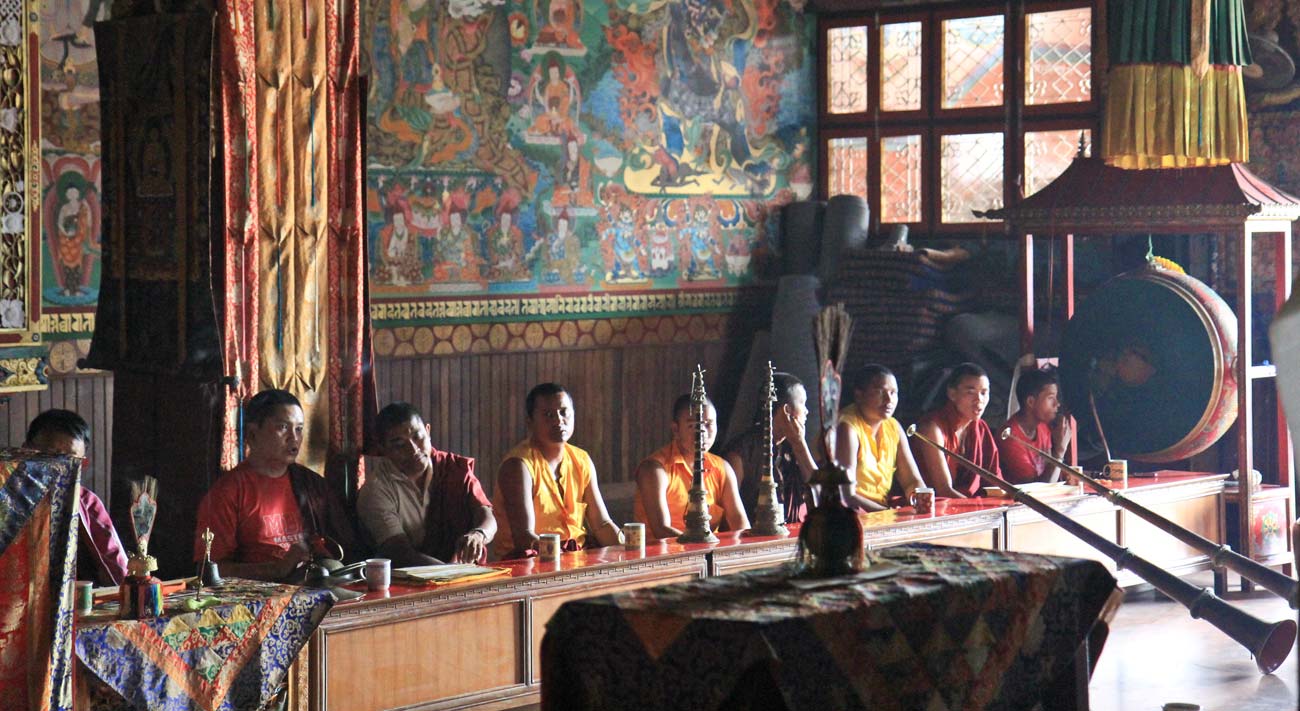

The chanting of religious texts accompanied by trumpets, drums, and cymbals, provides the setting for daily worship and meditation, here shown at Swayambhunath monastery, Kathmandu. Set on a monkey-infested hill, Swayambhunath is one of the oldest religious sites in Nepal, revered by Buddhist and Hindus alike. It is said to have been visited by Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE.

© Simon Edmundson.

As political unity suffered, Buddhism re-emerged. In the late 10th century, more than one hundred years after Langdarma’s assassination, Tibetans from both the west and east of the country who had remained faithful to the new religion returned to Lhasa and re-established Buddhism among the noble families.

In time, Buddhism spread to the general population. Monasteries proliferated creating an insatiable demand for Indian gurus and their teachings. Indian teachers were invited northwards, while Tibetan scholars journeyed to the universities of India for their own study and acquisition of Buddhist texts and learning. The next hundred years in this cultural metamorphosis would see an astonishing cast of legendary figures emerge from both Tibet and the plains of Bengal.

One of the great wonders of the world, the Potala Palace was built by the great 5th Dalai Lama, Lozang Gyatso, beginning in 1645. It was completed in 1694 twelve years after he died. The palace is named for the Potala hill on Cape Comorin at the southern tip of India, a rocky point there being considered sacred to Avalokitesvara, or Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva of infinite compassion.

© Wikimedia Commons User: Coolmanjackey / CC-BY-SA-3.0.

One such was Rinchen Zangpo, a young man from Western Tibet, who was dispatched by local rulers to seek the teachings of Indian masters in nearby Kashmir. Over a seventeen-year period during three separate trips, Rinchen collected texts and became the first of the great translators of Sanskrit texts into Tibetan. In between times, back in Tibet, he founded numerous monasteries and helped reinforce the supremacy of Buddhism over Bon. But there was no substitute for the genuine Indian guru. Rinchen suggested to his superiors that Atisa, the most celebrated of all Indian teachers, should be invited to Tibet. This would have required a copious outlay of gold. It would always take a certain amount of the precious metal, which Tibetan nobles had in abundance, to entice the Indian masters to make the journey and pass on their teachings.

Atisa was born into Bengal royalty in 982 but gave it all up to pursue the Buddhist way of life, learning it is said from more than 150 teachers and becoming master of countless sutras and tantra practices. He was particularly attached to an advanced form of tantra called Kalachakra. Meaning literally ‘Wheel of Time’, this tantra invokes a complex theory of cosmology and, not untypically in tantric practice, plenty of subtle body meditation including increasing engagements with a consort.

When Atisa was finally lured to Tibet in 1042 after countless entreaties, he was already sixty years old. He travelled towards Lhasa, taught widely for more than a decade and ended his life living in a cave near the capital where the faithful would visit him for instruction. Rare among Indian imports, he spoke good Tibetan and connected well with both the elite and the common peasant. For all their moral content, his teachings included plenty of magic for safeguarding ordinary life on the high plateau, such as preserving crops from hailstorms and the like. Atisa was instrumental in establishing Buddhism as the nation’s religion and remains one of Tibet’s most venerated figures.

A contemporary of Atisa from Bengal was Naropa, born into a high-class Brahmin family and like Atisa moved to quit a life of privilege and pursue the Buddhist path. Naropa had been instructed by a tantric guru called Tilopa, popularly known as The Great Magician. Forced to submit to twelve inhuman sufferings during his initiation by Tilopa, Naropa later acquired equal fame as a guru and taught at the University of Nalanda. One day, Naropa received and accepted as an initiate a young Tibetan called Marpa who had travelled to India via Nepal seeking religious instruction. Marpa stayed many years with Naropa and in turn became a celebrated guru and great translator of Indian texts. He reputedly returned to Tibet with a wife and seven female consorts. By all accounts his conduct was not beyond reproach. He was frequently drunk and quite ready to relieve his disciples of whatever possessions might be required to finance his next spate of wanderings. But this was all explained away by the fact he had by now acquired the status of a Bodhisattva, and his errant behaviour was simply testing his disciples’ faith in their guru.

Charles Bell (1870-1945) was appointed the British Political Officer in Sikkim in 1908 and charged with overseeing British interests in Tibet and Bhutan. He devoured Tibetan language and culture with the help of Sarat Chandra Das and hosted the 13th Dalai Lama (1876-1933) during the latter’s exile from Tibet after a Manchu incursion. The man standing centre is unidentified.

© Pitt-Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Marpa’s most famous disciple was another bad boy called Mila Raspa, born in central Tibet in 1052. Mila’s early years were not a great success. His father died when he was young, he abused his mother, and he eventually joined a gang perfecting the magic art of killing people. Mila learned the art well, trying it out during the wedding feast of a hated cousin and succeeding in finishing off thirty-five guests. As an encore, he summoned up a hailstorm that destroyed the village’s barley crop. Realizing that this might be taking things a bit far, he looked for help and, at the age of thirty-eight, found Marpa. Then followed a harrowing series of penances insisted on by Marpa to cleanse Mila’s waywardness. He was told to build a series of towers, and then tear them down returning the stones to where he had found them. He was then told to build a multi-storey tower that stands to this day. Marpa meanwhile would feign total disinterest in his pupil, often pretending to be too drunk to cast a glance in his direction. Finally, Marpa became satisfied that Mila Raspa was ready for initiation and his instruction began. Six years after meeting Marpa, an enlightened Mila Raspa headed home to find that all that remained of his mother was her dried bones. There and then he dedicated himself to a life of extreme asceticism.

And thus came about one of Tibet’s greatest legends — Mila Raspa in deep meditation in his cave subsisting year in, year out on the nettles that grew around him and ultimately attaining the unspoken dream of every guru — the state of Bodhisattva.

Mila’s sole item of clothing was a cotton garment that in time became shredded beyond repair. His wife and sister would bring him food and clothing and be shooed away for their trouble. According to his own word, it was simply through acceptance of the Buddhist concept of emptiness, shunyata, that he was able to sustain so much hunger, thirst and cold for so long. Yet amid this supremely ascetic existence, he would burst spontaneously into song, by turns insightful, melancholy and joyful.

© Simon Edmundson.

His ‘Hundred Thousand Songs’ remains a beloved text for Tibetans, of which this example was sung to his sister Peta on one occasion:1

And may they bless this hermit!

O sister, your affection leaves only sadness.

Since neither joy nor sorrow are permanent,

I beg you listen a while to my song.

If you consider my lair, I seem a wild beast.

At the sight of it, others would feel aversion.

If you consider my food, I seem a mere animal.

At the sight of it, others would just feel sick.

If you consider my body, I seem a skeleton.

At the sight of it, even an enemy would weep.

If you consider my conduct, I seem a madman.

At the sight of it, you my sister are sad.

But if you consider my mind, it is really enlightened.

At the sight of it, my former lamas rejoice.

The gritty gravel beneath me

Persistently pricks my skin and my flesh.

Inside and out my body has the nature of nettles

And is changeless in its greyish colour.

High in this lonely rock gorge

Nothing eases my constant melancholy,

And such melancholy is inseparable

From the enlightenment of holy lamas.

As a result of my great effort

There is no doubt my spiritual understanding grows.

O Peta, do not be sad, but cook some nettles!

Mila Raspa nevertheless had time for some travel and teaching, and one disciple in particular, called Gampopa, would continue the lineage that had originally started with Tilopa. This would develop a critical mass of followers and eventually constitute the Tibetan Buddhist tradition called Kagyu-pa, or ‘Oral Tradition’. An offshoot of this order called Drukpa would become dominant within Bhutan.

By this time, towards the end of the 11th century, Kagyu-pa was one of three distinct orders or traditions in Tibetan Buddhism. The original introduction of Buddhism by Santaraksita and Padmasambhava, and incorporating some Bon tradition from that time, was known as Nyingma-pa, literally the ancient school. To keep up with the state of play among the other schools, the Nyingma-pa school benefitted from hidden texts, called terma, supposedly written and concealed by Padmasambhava and his inner circle of twenty-five disciples. The ancient tradition could therefore be given a sort of makeover whenever one of these hidden texts was discovered.

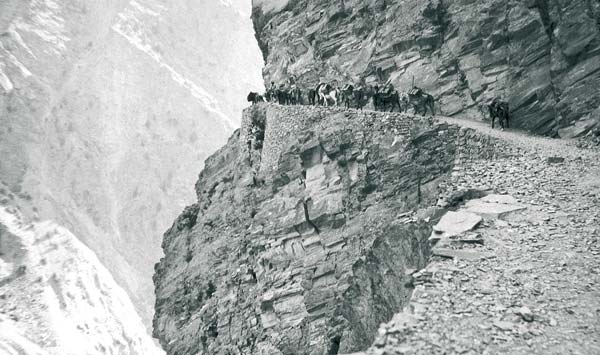

Giuseppe Tucci (1894-1984), the great Italian Tibetologist, with his caravan on the Zoji La, the 11,500-ft thoroughfare connecting Kashmir and Ladakh, and ultimately western Tibet. This expedition of 1931 was his first at such a large scale. During the following years, he returned regularly to document Tibetan culture, religion and art. Photograph probably by Tucci himself.

© Artenomade Edition, Macerata, Italy.

The other order was the Sakya-pa school, born out of a prosperous monastery situated on a key trade route to Nepal at Sakya in central Tibet. Whereas the lineage in the Nyingma-pa and Kagyu-pa schools passed from guru to pupil, the lineage in Sakya-pa remained in the noble family that founded it and indeed remains with that family today.

The 11th century thus saw Tibet transform into a Buddhist powerhouse. The transference of Buddhist texts and knowledge from India to Tibet would continue for another century. But come the 13th century, Tibet suddenly found itself the sole guardian of the Vajrayana tradition. Muslim hordes were invading India and in short shrift destroyed every vestige of Buddhist culture there. Nalanda and other university sites were sacked, and the original Sanskrit sutra and tantra texts disappeared without trace. Tibet, through three centuries of constant acquisition of manuscripts and scrupulous translation, had now become the custodian of a culture initially taught to them by Indian gurus …. [BUY THE BOOK TO READ ON]