Science

THE PLATES MUST SPEAK

The sample text below is a shortened extract from the prologue to the second section in the book. For a full list of the book’s contents please see here.

Prologue:

Caught by a Quake

It is spring 2015, and we are traversing a section of the Nepal Himalaya, starting in Solo Khumbu, the area encompassing Mount Everest and several other giants, and continuing through an area of central Nepal called Rowaling. We will finish at the main road connecting Kathmandu with Tibet. Altogether a three-week walk in a roughly westerly direction.

My trusted companions are Jacques, who lives near Lake Annecy and with whom my wife Connie, our son Simon and I had traversed the Upper Dolpo area of Nepal three years previously; Phu Dorje from a distinguished Sherpa family living in Phortse, a small village four hours on foot north-east of Namche Bazaar, the trekking centre of Solo Khumbu; Mani, another companion from the Dolpo traverse, a porter of small stature, incredible endurance and good nature, recently married; his brother-in-law Sandjip; and Ze, a highly recommended Rai porter from the east of the country.

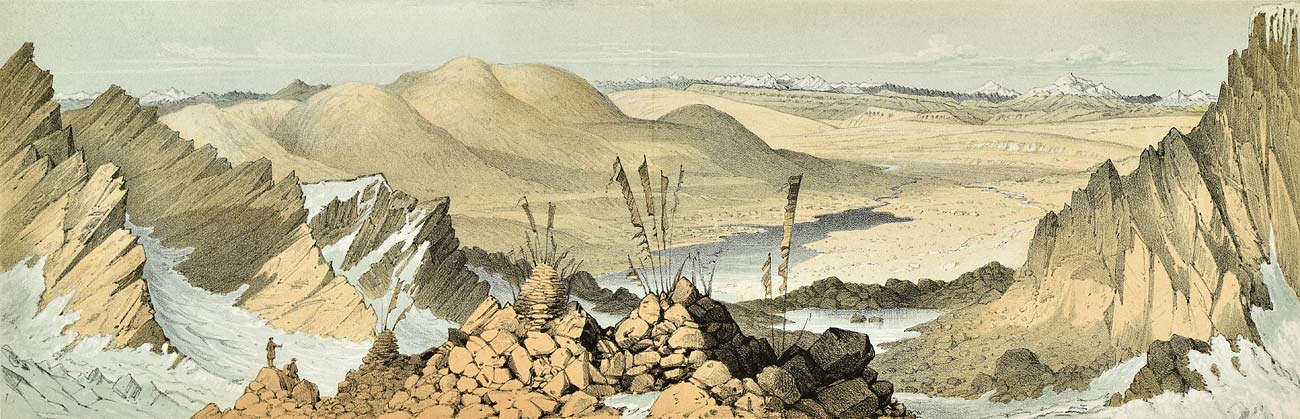

One day before the earthquake, descending from Gyoko to Dhole.

© Henry Edmundson.

This is my second trek with Jacques. Besides being a stronger walker than myself, Jacques has an incredible ability to eat double portions of dal bhat at speed. Dal bhat, literally ‘lentil rice’, is the staple twice-a-day diet of the Nepalese. These two ingredients are mixed with fried-up vegetables, whatever is locally available. Every now and then, I try and match him, but can never get the stuff down quickly enough. Even for committed meat eaters like us, dal bhat keeps the body, legs and lungs going more or less indefinitely.

Standing, left to right: Vittorio Sella, Federico Negrotto, Filippo De Filippi (geologist). Seated, left to right: His Royal Highness the Duke of the Abruzzi, Lady Helen Younghusband, Madam De Filippi, Sir Francis Younghusband. This remarkable photograph dating from 1909 by the renowned photographer Vittorio Sella shows the meeting of two great Himalayan protagonists, the Duke of the Abruzzi who led the Italian claim to the Karakoram’s highest peak, K2, and Sir Francis Younghusband, the most prolific player of the Great Game and the first European to traverse the Karakoram from Central Asia to India.

© Fondazione Sella, Biella, Italy. Courtesy, Fondazione Sella, Biella, Italy.

Jacques’ sleeping also works like clockwork. He doesn’t mind if there is a light on while I read. He just immerses himself in his wonder sleeping bag, closes two noisy and rather irritating zips with a flourish and is off in cuckoo land in a matter of seconds. He loves his bag. He reminded me on one occasion: “Every stitch in this bag was made in the homeland, whereas the competitive brand, while designed in France, was manufactured somewhere else.” The zips cause me much anguish. Being older men, though rarely admitting to it, we need multiple excursions each night to relieve ourselves. I use a plastic flask, but Jacques enjoys exiting his cocoon to seek the great outdoors. This requires much unzipping and zipping, each time slicing decibels through the darkness.

Phu Dorje is in his mid-thirties, with wife and two small children installed in Kathmandu. Phu’s younger brother Tashi co-founded the agency that is organizing the trip. But Tashi died on the 8,163-metre peak Manaslu in central Nepal four years ago. With a couple of French climbers, one being a guide, they made it to the top, but only just. From the summit, Tashi phoned Ang Tsering, his business partner and agency co-founder, to say that the French were in bad shape. That was the last that was ever heard from him. A rescue ensued with Phu in charge. Suspended from a rescue helicopter, Phu looked into every likely crevasse on the mountain and eventually in one crevasse found his brother, but there was never any sign of the French. Tashi was retrieved, his body remarkably intact, and ceremonies were held in Kathmandu and the family village of Phortse. Untypically for a Sherpa, Phu is rather rotund, but he has nevertheless climbed Everest four times.

Rather than take the plane to Lukla, a precarious landing strip cut into the side of a mountain and two days march from Namche Bazaar, we opt to walk in from the roadhead at Salleri, an eight-hour jeep drive from Kathmandu. This variation adds three days of up-and-down walking but has the merit of avoiding possible congestion at Lukla, where weather often disrupts the plane schedule. It also gives me the opportunity to relive a piece of the 1953 Everest expedition, because we will be travelling along the very path taken during their long approach march to Everest basecamp.

In 1849, Hooker and his companion in Sikkim, Dr Archibald Campbell, reached the Donkia Pass in north-east Sikkim close to the Tibetan border, elevation 18,500 ft. They were astonished to find sea shells in the nearby Tso Lhamo lake. Coloured mezzotint by W. L. Walton, from Himalayan Journals by Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1854.

© Geological Society of London.

We leave Kathmandu in mid-April through its filthy suburbs and then drive eastwards on the usual mix of tarmacked road, dirt tracks and occasional riverbeds. Eventually we cross the Sun Kosi river that we have been tracking and start a long climb. The driver is skilful and goes fast. At one point, the mountainside is covered in flowering rhododendrons, deep red at first and then multi-coloured. We go up and down, past innumerable police check posts, and arrive at Salleri (2,390 metres) by mid-afternoon, checking into a rabbit warren of a guest house. Soon, Mani arrives with his brother-in-law Sandjip, who looks about fifteen years old, they live in a nearby village. Mani, our hero from the Dolpo crossing four years before, has a gold ring in one ear and looks great. We consume a good dose of dal bhat and go to bed early.

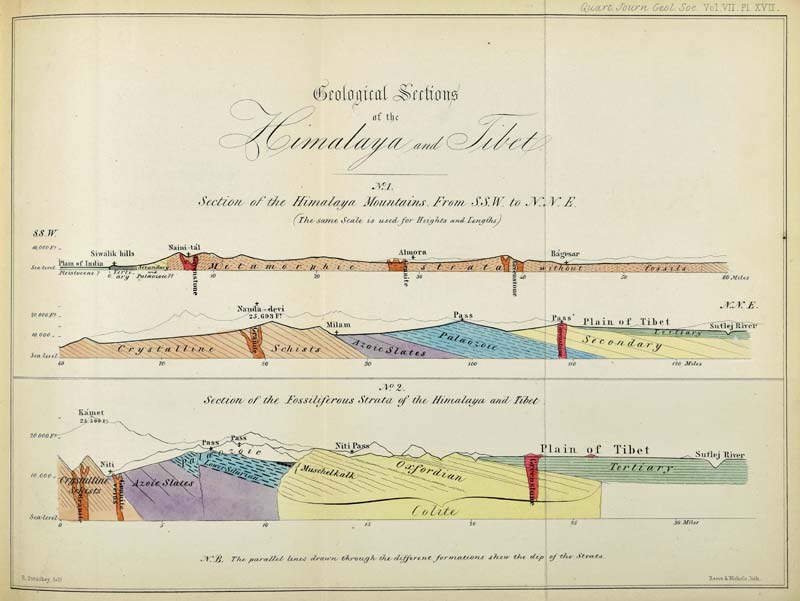

Strachey’s traverse of the Himalayas and return to the Indian plains took barely two months. Yet he and his companion James Edward Winterbottom found time to catalogue meticulously everything they observed. Strachey’s geological observations were particularly noteworthy. Amid the jumble of Himalayan peaks and valleys, he was the first to make the key observation that Himalayan rock strata generally dip downwards to the north-east. His rudimentary geological cross-section would impress geologists many decades later. From On the Geology of Part of the Himalaya Mountains and Tibet by Richard Strachey, Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, 1851.

© Geological Society of London.

The next three days are spent traversing the foothills northward towards Solo Khumbu, a peaceful meander along ancient paths, up one pass, down to the next valley, and then up again in a sort of slow-motion joy ride. The weather is mixed, but the rhododendrons are in full bloom … and the cuckoos! I remember this trek for their clear song heard throughout the approach march and subsequent retreat. On the trail, I debate in my mind whether the beauty of their song compensates for their appalling behaviour in the nest.

We stop every night in a lodge. Over tea one afternoon, I show Phu a picture of Connie, and to our mutual amazement he recognizes her! It seems we had crossed paths four years before in Dolpo. He was leading a French group that we had met and exchanged pleasantries with for perhaps five minutes. I ask Phu if he remembers me from that occasion. “No” is his answer, and everyone laughs.

After two more days, we find ourselves in a deep valley hundreds of metres below Lukla, where the famous airstrip receives most of the trekkers heading for the Everest area. We can hear the activity, a continuous buzz of helicopters, but not many planes because the weather has closed in. In a torrential downpour, I buy an umbrella at a small shack on the side of the path for 300 rupees and soon discover that I can’t have the umbrella up and also wear my hat — a Panama, not worn for effect, but because it provides excellent shade and doesn’t get blown off my head. Fine-tuning your kit is a never-ending ritual.

So far, we have met no other trekkers, but the path is busy with local traffic and saturated with donkey trains carrying supplies to Namche Bazaar. Each village has a donkey park, where the donkeys can rest, yet be prevented from roaming around the village. Usually there are two men in charge of each donkey train, each train consisting of perhaps ten donkeys, one man in front and one at the rear. There always seems to be one donkey trailing behind the second man, maybe a senior member of the team with the privilege of going at its own pace. You can always guarantee that just where the path becomes especially precipitous, two donkey trains moving in opposite directions will meet.

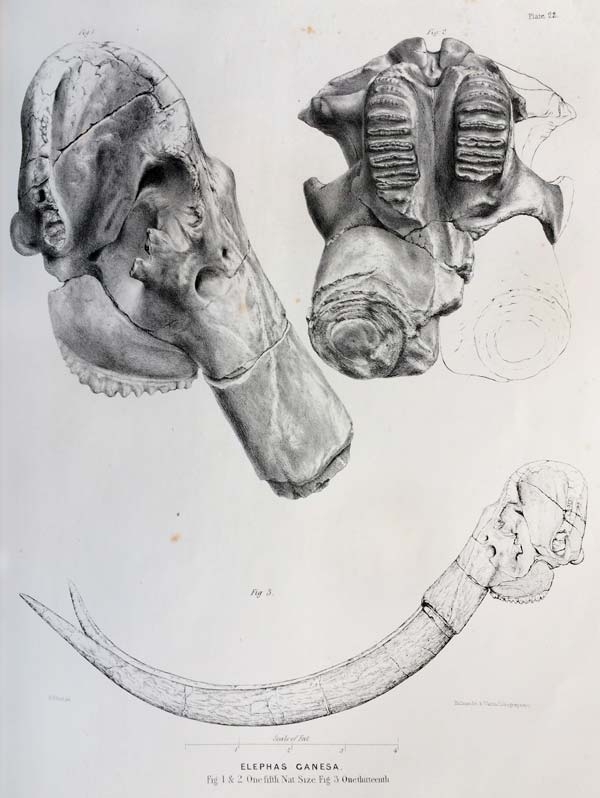

Two Victorian fossil hunters, Hugh Falconer and Proby Thomas Cautley, met in Saharanpur in north India around 1830 and embarked on an extraordinary fossil-hunting campaign in the Siwalik foothills of the Himalayas. They unearthed a complete menagerie of prehistoric mammals, proving that the foothills had been formed in comparatively recent times. Etching from Fauna Antiqua Sivelensis, being the Fossil Zoology of the Sewalik Hills, in the North of India by Hugh Falconer and Proby Thomas Cautley, 1846.

Courtesy of the Zoological Department, University of Cambridge.

We are now on the main Everest trekking thoroughfare, and reach Namche in another two days. This thoroughfare on the Everest basecamp trail is getting ever more sophisticated with an Irish Pub showing Premier League football matches. What is the world coming to, we think, without saying anything. Namche is at 3,440 metres, but Jacques and I are already reasonably acclimatized. Nevertheless, we occupy the following rest day with a short climb to Khumjung village for a famous view of Everest and then visit the local school founded by Edmund Hillary.

The next day, we set off northwards towards the Nangpa La, an historic and much travelled pass between Nepal and Tibet, now closed by the Chinese. We take a beautiful path through pine trees towards Thame village, while Phu tells me about growing up in his village of Phortse. He remembers seeing Tengboche monastery burn down when he was about nine years old; this famous monastery, since rebuilt, lies on the opposite side of the valley from Phortse on the main highway to Everest. He later became a monk there. The monastery theme continues all morning. We pass a monastery for women, then the Thame monastery whose lama died four years ago. Phu explains that they have just found a six-year-old near the village of Monjo as his reincarnation, and he will be installed this summer. I ask what happens if the boy doesn’t appreciate the life change. Phu says that he will love it because he already is the lama. I make a note to get my head around the realities of reincarnation.

Phu walks slowly, but I have the feeling he could maintain the same pace at 8,000 metres. We are really in among the mountains now, heading for the Renjo La at 5,360 metres as part of our acclimatization. We do a double day, meaning forcing two days march into one, and spend the night at a primitive lodge at a height of more than 4,300 metres. We set off early the next day inching our way up to the col in deep snow with the porters trailing some distance behind. We have lunch on top and decide that Jacques should wait for them. Phu and I go down, reaching the snowbound village of Gokyo, pretty shattered, me that is.

There is no sign of Jacques and the porters after a considerable time, so someone is sent up with tea. After an eternity the team are sighted. Sandjip apparently got a bad headache just near the top, and Mani carried most of his load down, Jacques also took an extra pack. We give Sandjip paracetamol and consult with a young doctor couple from New Zealand permanently based in the village during the trekking season. Acute mountain sickness, which is potentially fatal, is the diagnosis, so we rethink plans and decide to return towards Namche. But we hope to skirt it and then head westwards for the main purpose of the trek, a traverse through the Rowaling area.

The walk down the Gokyo valley is spectacular, with views of Cho Oyu (8,188 metres) behind us, which brings back memories of nearly climbing it many years earlier. We stop at Dhole and settle into a lodge run by a man who cooked for Tashi’s memorial ceremony at Phortse. Some yaks are grazing a pasture next to us, and one picks up a baby yak with its horns and tosses it aside to eat the grass it was sitting on.

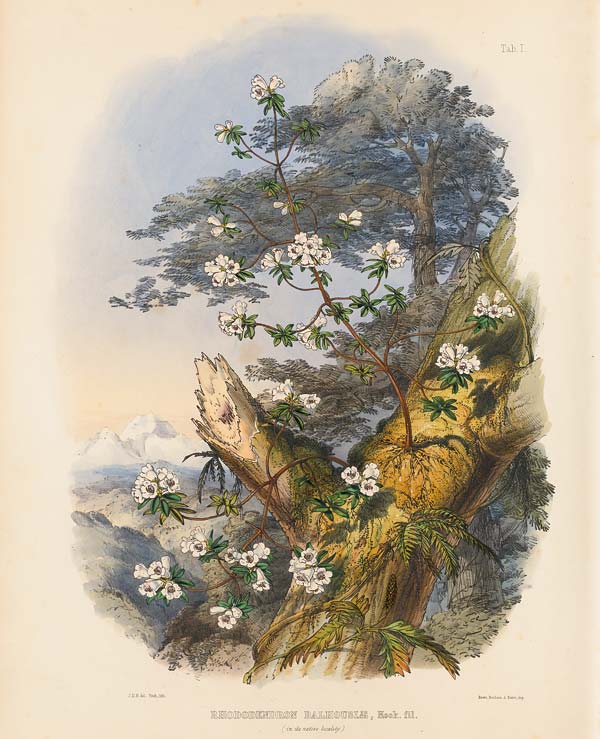

Hooker’s masterwork Rhododendrons of the Sikkim-Himalaya was assembled by his father from manuscripts, sketches and plant samples sent home via Falconer in Calcutta. The lavishly illustrated book was published in 1849 while Hooker was still in the field. It launched a rhododendron craze; this particular variety first flowered in Britain in a hot house on the Earl of Rosslyn’s estate in 1853. Hand-coloured lithograph of Rhododendron Dalhousiae by Walter Hood Fitch, based on a watercolour sketch by Joseph Dalton Hooker.

© Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

The next day, April 25, it is snowing. Starting down after breakfast we see a musk deer, the national animal of Nepal, and reach a hovel, which is home to a young woman and three small children. This is the house Phu grew up in and it is still owned by his father; the woman is the wife of the man who ran the lodge we just came from. It’s a small world here in Solo Khumbu. We then climb three hundred metres straight up to the Mon La and take an incredibly steep staircase down a cleft in a cliff to Khumjung. Still snowing hard, we stop at a lodge for lunch just near the Hillary school.

As we eat, we hear a rumbling sound that slowly increases in intensity, as though a hundred large trucks are heading straight at us. For a moment we remain stuck in our seats unable to react. But when the noise becomes deafeningly loud, instinct takes over and we rush out of the lodge and seek a large flat area. Suddenly, the earth vibrates violently beneath our feet, and the stone walls of houses start collapsing. About a minute later, the vibration subsides. There is debris everywhere and many houses are destroyed — but not our lodge. We go back inside and unbelievably I connect to the internet, send a mail home, and pick up news that a huge earthquake has hit Nepal. Then the rumbling sound starts again, and we rush out a second time. The next shock is less strong than the first but still strong enough. People are screaming, and children cry. Our hostess sticks her tongue out to express her terror and disbelief.

It takes a while to comprehend that nothing is as it was. Phu says he should go immediately to Phortse to check that his family are alive, and that the rest of us should follow. He rushes off. Three hours later as the rest of us approach Phortse, there is another tremor and we notice that on the village stupa the Buddha has lost half his face.

Phu’s family have escaped injury. We are welcomed into the family home, which seems intact, and a celebration of merely being alive seems to be in the air. A stove is brought into the downstairs room, and a chimney is threaded in pieces through three floors up to the roof. Around the fire, we eat dal bhat with chicken and copious chang and beer. Phu’s father, a celebrated Sherpa in his day, presses the hot chang on us. Phu explains that the earthquake was caused by a large bear turning in his sleep deep underground. During the night, a tremor shakes our beds — we haven’t yet learned to sleep outdoors.

The Trailokya Mohan Temple, dedicated to Lord Vishnu and built during the Malla dynasty in 1679, lies in ruins (right). The Gaddi Durbar Palace built by the Ranas in neo-Greek style in 1908 (left) appears unscathed although the building’s fabric was later found to be seriously compromised. Numerous other early temples were destroyed.

© Bernat Armangue / AP / REX / Shutterstock.

In the morning, we say our thanks and goodbyes and descend to the river, where we meet the man who ran the lodge at Dhole, where we had stayed two nights ago. He says his lodge is completely destroyed. In an effort to preserve a sense of normality, he is taking his young girl to the weekly boarding school in Khumjung. We learn later that the boarding house is no longer standing. We continue down to Namche to collect ourselves. It is still snowing, and mist fills the valleys. On the way we pass a man being transported on a makeshift stretcher. Nobody is talking. We all feel hostage to the shocking events of yesterday.

Back in the lodge at Namche, which is still intact, I manage to phone Connie for the first time, exchanging news, when suddenly there is another large tremor. The lodge twists and groans like a ship at sea. I rush outside and stand by a wall that flexes like a thin piece of plywood. A minute later, all is calm again. By now the weather is clearing, and we hear incessant helicopter traffic heading for Everest. A rumour spreads that there are many deaths at Everest basecamp. As night falls, the whole of Namche decamps to any available flat and open space. We join a throng on the school playground and pitch our tents. A huge group sheltering under a tarpaulin alongside chant in prayer …. [BUY THE BOOK TO READ ON]